Learn How to Format a Screenplay: Step-by-Step Guide

Written by MasterClass

Last updated: Aug 30, 2021 • 8 min read

A screenplay is a blueprint for a feature-length movie, short film, or television show, and it is the first step in taking your story from page to screen.

Learn From the Best

What Is a Screenplay?

Also called a script, a screenplay is a written document that includes everything that is seen or heard on screen: locations, character dialogue, and action. From the first draft to its final incarnation, a screenplay tells a story. However, it is also a technical document that contains all the information needed to film a movie.

What Does the Screenwriting Rule “Show, Don’t Tell” Mean?

Unlike a novel, which can illuminate a character’s interior thoughts or spend time describing a setting or place, a screenplay should only contain information that you can “show” on screen.

This means that if a character is feeling sad, you must find a way to show that they are sad. For instance, instead of writing, “Jessica is sad because she thinks her cat is missing,” write a scene where the character cries and hangs a sign for a missing cat.

How Long Should a Screenplay Be?

In a screenplay, one page roughly equates to one minute of screen time. This means that as a general rule of thumb, screenplays typically run from 90 to 120 pages long.

Screenplays are made up of many scenes, and each scene can be as short as half a page or as long as ten pages. However, most scenes are usually three pages or less.

What Font Is Best for Writing a Screenplay?

For easy readability, and to ensure the “one page per minute of screen time rule” always holds true, screenplays have specific formatting requirements.

One important element of script formatting is font. It is essential that the font used to write a screenplay has consistent spacing.

As such, most screenplays are written in Courier font, 12-point size, single-spaced. Courier is a “fixed-pitch” or monospaced font, which means that each character and space is exactly the same width.

What Are the Right Screenplay Margins?

In keeping with the one page = one minute rule, screenplays follow these industry standards for margins:

- The top and bottom of every page should have a 1-inch margin

- The left margin should be 1½ inches, so that there is room for the hole punch to go through when the script printed

- The right margin should be 1 inch

- These margins result in roughly 55 lines per page (not including page numbers)

How Should You Format a Screenplay?

All screenplays are formatted in roughly the same way. Although you can play within the format, generally speaking, screenplay formatting consists of:

- Scene headings

- Action lines

- Characters

- Dialogue

- Parentheticals

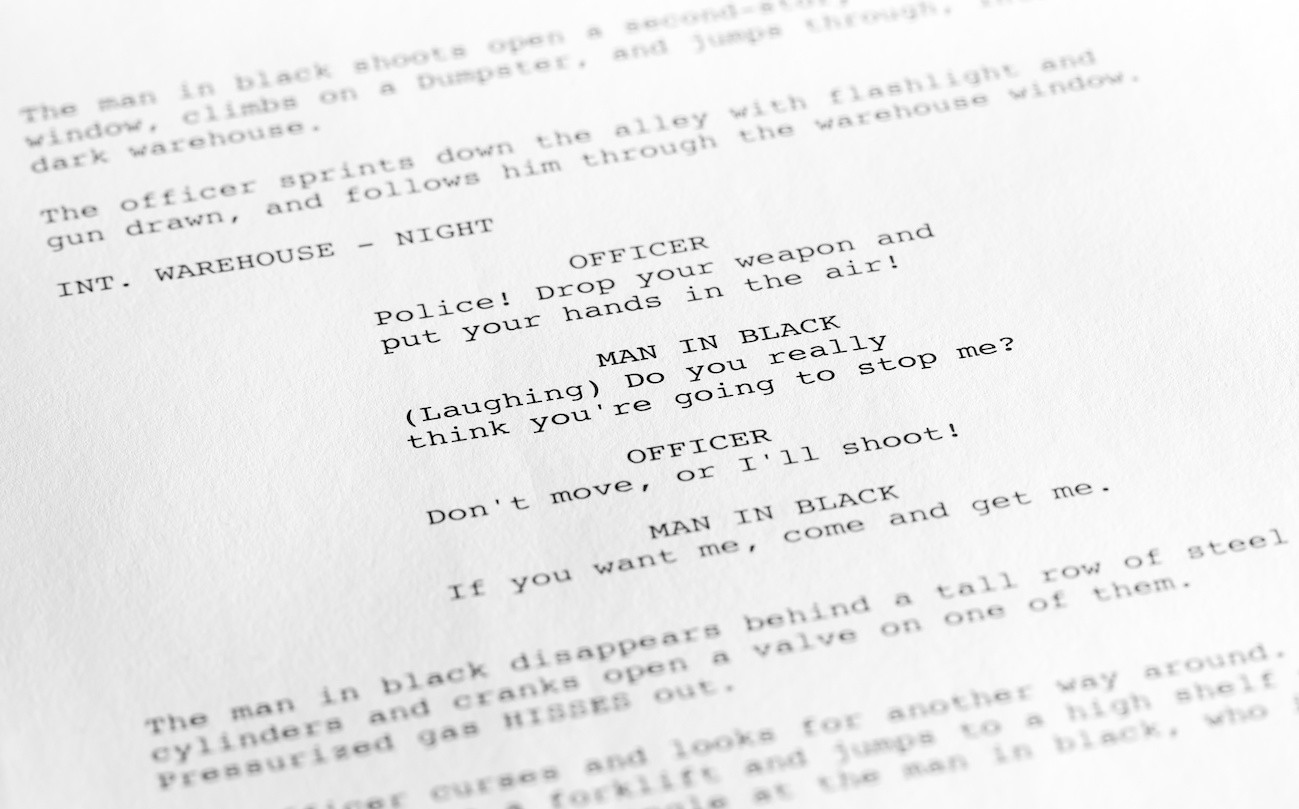

How to Format a Screenplay Step 1: Scene Headings

Also called a slugline, a scene heading tells us where we are in the world of the film, and what time of day it is. For instance, “INT. POLICE STATION - NIGHT” lets the audience know that we are on the interior of a police station at night.

Scene headings should always be capitalized (they may also be bolded), and should always be brief. Some writers utilize a two-part scene heading. For example: “INT. POLICE STATION - BATHROOM - NIGHT.” This kind of slugline is commonly used in films that might have a lot of scenes in the same location, like a house, and is used to differentiate between the rooms.

Though it’s optional, some writers will use a combination of scene headings and subheaders to indicate setting. Subheaders are essentially truncated scene headings. For instance:

In the example above, the truncated scene headings help indicate the quick changes in location while maintaining the pace of the scene. However, if you prefer the traditional method, you could just as easily write full scene headings for every new room in the house Megan walks into.

How to Format a Screenplay Step 2: Action

Also known as scene description, action lines describe character movement in a scene, but they can also describe anything the audience can see on the screen. In screenplay format, action lines are always written in the present tense. For example: “The science lab is empty. Jose squats behind a lab station. He grips his knife behind his back.”

You can capitalize, underline, or italicize certain words or phrases within action lines for added emphasis. Major props are often mentioned in all caps or an emotion might be emphasized with an underline. For example:

How to Format a Screenplay Step 3: Character

All characters should be introduced before their first line of dialogue. Each time a new character is introduced, their names should be written in all caps.

Any minor or ancillary characters should be introduced in caps as well, even if they don’t have any lines: HENCHMEN, BARTENDER, ANGRY TEACHER. (One exception to this rule is when the people are part of the action or setting.

For instance, if you are writing a chase where a car plows down a street full of people, you don’t have to write “people” in all caps, as they are not characters, but rather part of the action.)

Most characters are introduced with a bit of information about their personality, age, or appearance to help paint a mental image for the reader and guide the casting directors to find an actor who fits the part. This information can be added in one of two ways:

- In parentheses after the character’s name. “TIMMY (21, bleach blonde hair, eyebrow piercing).”

- As part of an action line. “TIMMY (21) jumps off his skateboard, wiping his bleach blonde hair out of his eyes to reveal a series of eyebrow piercings.”

How to Format a Screenplay Step 4: Dialogue

Any time a character speaks, whether out loud or in voiceover, their lines must appear as dialogue. Dialogue is centered on the page, one inch from the left margin. The name of the character who is speaking should always appear in all caps above the line of dialogue.

You can add a qualifier next to the character’s name if the dialogue is meant to be heard in voiceover (V.O.), or when a character is present, but they are not seen on screen (O.S. for off screen, or O.C. for off camera). For example:

Finally, if a character’s dialogue spills over from one page to another, you can add a qualifier for this as well (CONT’D, for continued).

How to Format a Screenplay Step 5: Parentheticals

Finally, if it isn’t clear from the dialogue itself, parentheticals can be placed beneath the characters name and above or between lines of dialogue to indicate how something is meant to be performed.

A parenthetical can be used to add a pause between two lines, indicate singing or shouting, or provide an adjective that indicates that suggests tone. For example:

What Should Not Be Included in a Screenplay?

When writing and formatting your screenplay, here are four mistakes to avoid.

- Overly elaborate scene description. A screenplay is a recipe, not a menu. That means your action lines should describe the events taking place as simply and efficiently as possible. Avoid using overly ornate or poetic language to describe your scenes, particularly if that language isn’t visual.

- Too many parentheticals. While you may have a vision for your characters, it’s ultimately the director and actors’ responsibility to interpret a screenplay and decide how to portray a particular scene or moment. For this reason, avoid using parentheticals unless it’s absolutely necessary for a scene.

- Too many transitions. Similar to the above, it’s largely the editor’s job to decide how to transition from one scene of a finished film to another, not the writer’s job. Some transitions may be useful in foreshadowing action or revealing character. Most of the time, however, a new scene heading is enough to signal a new scene.

- Camera angles. Screenplays (especially spec screenplays) typically don’t include camera angles or information for how to shoot a scene, as that is the domain of the director. Just describe what you want to see on screen (i.e., “A giant tear runs down the clown’s face”), and the director and cinematographer will decide what kind of transition or angle they need (i.e., a close-up shot of the single tear running down the clown’s face).

What Is the Difference Between a Spec Script vs. a Shooting Script?

Hollywood and other film industries use two different types of scripts: spec scripts, and shooting scripts. Each has slightly different content and formatting elements that suit its purpose.

- Spec script. This is a type of script written specifically with readers in mind. Spec scripts are written “on speculation”—that is, a writer creates a spec script hoping (or speculating) that it will be optioned, purchased, and ultimately produced into an actual film. With that in mind, spec scripts don’t contain any technical information about the screenplay should be filmed or edited.

- Shooting script. Once a spec script has been “greenlit” for production, a new script is created as a practical reference for the production crew. In addition to any rewrites that have been done on the spec script to suit a production’s constraints, a shooting script will also contain additional information about how and where scenes will be filmed, along with credit sequences, scene numbers, and other elements that don’t concern a spec writer.

Can You Write a Screenplay in Microsoft Word?

Microsoft Word has a “screenplay template” that you can download for free from the Microsoft Office website. Once the template has been added to Word, simply open a new “screenplay template” and start writing. The standard Microsoft Word toolbar will automatically update to reflect common screenwriting needs, like toggling between dialogue or action lines.

What Are the Best Screenwriting Software Programs?

There are many excellent programs from web-based applications to downloadable software that can format your screenplay for you. Popular screenwriting programs include:

- Final Draft

- Celtx

- WriterDuet

- Movie Magic Screenwriter

- Fade In

- Highland

- Scrivener

- Screenplay Formatter (a Chrome extension for Google Docs)

Want to Become a Better Screenwriter?

Whether you’re a budding filmmaker or have dreams of changing the world with your screenplays, navigating the world of film and television scripts can be daunting. No one knows this better than Shonda Rhimes, who, when she pitched Grey’s Anatomy, she got so nervous she had to start over—twice. In Shonda Rhimes’s MasterClass on writing for television, the celebrated creator and producer of some of TV’s biggest hits reveals how to create compelling characters, write a pilot, pitch an idea, and stand out in the writers’ room.

Want to become a better filmmaker? The MasterClass Annual Membership provides exclusive video lessons from master filmmakers, including Shonda Rhimes, Judd Apatow, Martin Scorcese, David Lynch, Spike Lee, Aaron Sorkin, and more.