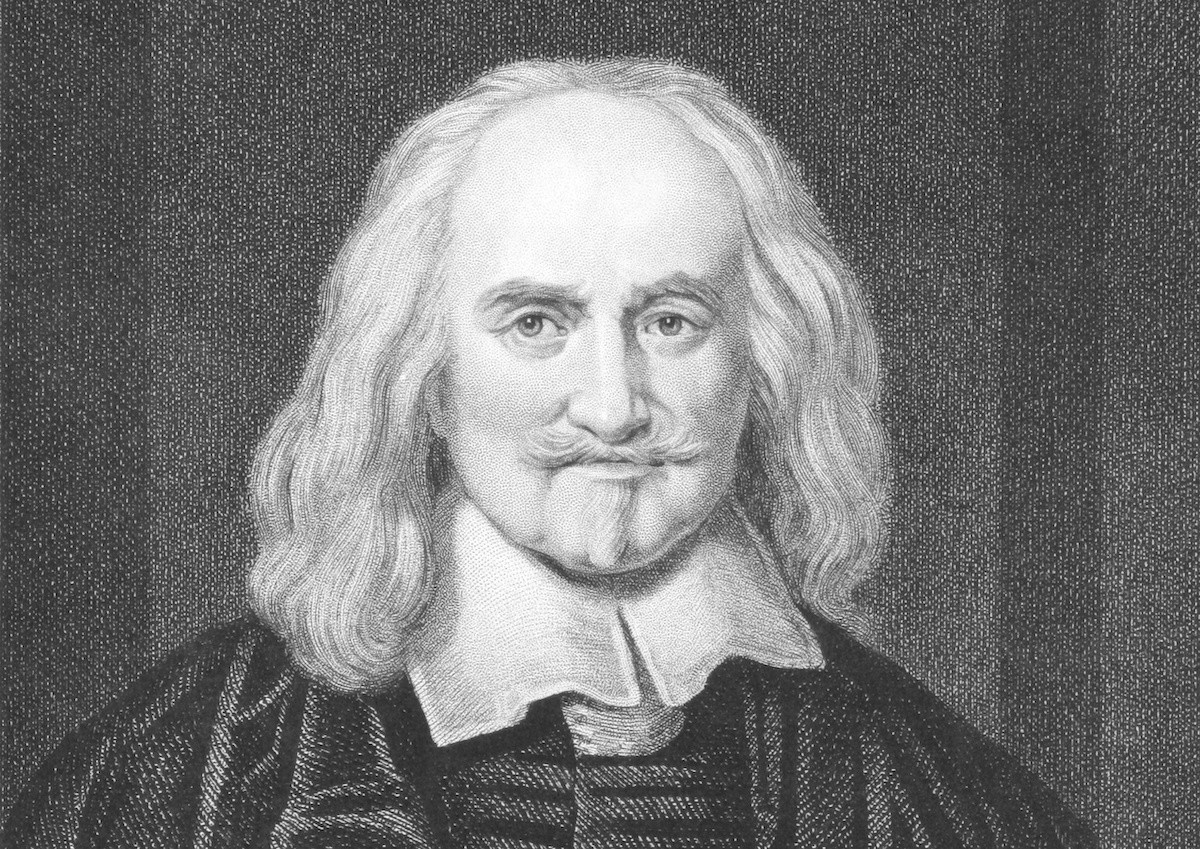

Thomas Hobbes: Philosophy and Works of Thomas Hobbes

Written by MasterClass

Last updated: Oct 17, 2022 • 5 min read

Thomas Hobbes’s ideas on a range of topics, particularly political theory, have greatly influenced philosophy.

Learn From the Best

Who Was Thomas Hobbes?

Thomas Hobbes was an English philosopher who wrote on several topics that would come to dominate the political and philosophical discourse, such as liberty, natural rights, human nature, civil law, and social contract theory. In the history of philosophy, he is best known for his work on political theory, which was crucial to the development of the Enlightenment.

A Brief Biography of Thomas Hobbes

As with many of the intellectuals of his day, Hobbes’s work covered a wide range of interests, and he wrote on a great many topics. Many subsequent philosophers, including Leibniz and Kant, had an interest in his writings. The following is a brief biography of his life:

- Early years: Thomas Hobbes was born in 1588 in Malmesbury, Westport, in what is now Wiltshire, England. Hobbes excelled as a student and was fluent in Greek and Latin. He studied at Magdalen Hall—which would later become Hertford College, Oxford—then transferred to Cambridge, earning a B.A. in 1608. In 1628, he translated Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War, the first English translation of an original Greek manuscript.

- Tutoring and patronage: Hobbes served as a tutor to the son of William Cavendish, Baron of Hardwick (later Earl of Devonshire). His connection with this prominent aristocratic family was a significant feature of Hobbes’s life. Through the Cavendishes, Hobbes met playwright Ben Johnson and the philosopher Francis Bacon. William Cavendish was a supporter of Charles I in the English Civil War, and this connection to royalty influenced Hobbes’s political philosophy.

- Paris, France: From 1631 to 1637, Hobbes spent most of his time in Paris. This departure, and an earlier trip throughout Europe from 1610 to 1615, increased his breadth of knowledge and led him to a more intensive study of philosophy. In Italy, he met with Galileo, and in Paris, he was a regular participant in philosophical discussions led by Marin Mersenne.

- Return to England: In 1637, Hobbes returned to a divided England. Civil War was brewing, and attitudes about politics were highly charged. Hobbes continued to elaborate his political thought, completing The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic in 1640 and engaging in a sustained argument with the work of René Descartes. He also began working on De Cive, which would be published in 1641. Controversy over his work and tumult throughout England, which culminated in the Long Parliament, led to his returning to France once again.

- Civil War in England: With the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, Hobbes became acquainted with English royalists who had fled across the English channel to France. His interest in politics was rekindled, and he re-circulated De Cive, which became popular in royalist circles. He also published Leviathan, his most important work of political theory, in 1651. Despite his royalist influences, many of his contemporaries were outraged by the work, leading him to return to England, where he successfully appealed to the revolutionary parliament in London.

- Last years: Hobbes composed an autobiography in Latin verse and completed English translations of The Odyssey and The Iliad in 1675. He also wrote a history of the English Civil War called Behemoth, which was published posthumously. He lived out the rest of his life at the Chatsworth House estate, with support from the Cavendish family.

5 Central Ideas of Hobbes’s ‘Leviathan’

Hobbes is chiefly known for his political philosophy. His work as a theorist is expressed most fully in Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil, more commonly known as Leviathan (1651). The original edition of the book has a much-reproduced frontispiece that illustrates the following ideas:

- 1. Laws of nature: In building his view of politics, Hobbes begins with imagining what he called the state of nature or the natural condition of human beings before the government. Under natural law, everyone would have an equal right to everything, so a condition of war with everyone fighting for their self-preservation would ensue. This particular pessimism about the state of humanity is described as “Hobbesian.”

- 2. The social contract: To avoid this state of war and the constant risk of violent death, people naturally develop a social contract, which is the beginning of civil society. In Hobbes’s view, the most desirable version involves a solid central authority, such as absolute sovereign authority. Since a king was responsible for ensuring peace and stability, everything in the kingdom belonged to him.

- 3. Central authority: This preference for a central, sovereign power was the main thrust of Hobbes’s work as a political philosopher. Leviathan outlines that the sovereign should not interfere in the lives of ordinary people and that the King should create rules to promote peace. Later philosophers, most significantly John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, built upon these aspects of Hobbes’s political science. In particular, they added the right to rebellion, believing that the subjects could overthrow the absolute sovereignty if the ruler wasn’t behaving justly. These and other later ideas led to modern democracy, where members of society shared power.

- 4. Materialism: Hobbes was one of the most prominent materialists of his time, stipulating that humans were nothing more than matter. Unlike Aristotle, who, like Plato, was a significant influence on intellectual culture in Hobbes’s day, Hobbes did not believe that there could be something separate from the physical world.

- 5. Morality: Hobbes’s writing is against the notion of free will and promotes the idea that good and evil are relative categories defined by pleasure or pain. In this respect, he had some commonalities with Spinoza, another prominent thinker of the day.

Not all of Hobbes’s writings were influential. De Corpore (1655) contained an erroneous proof of squaring the circle, a geometric puzzle he believed he’d solved. De Homine (1658) was an elaborate theory of vision, although it didn’t prove nearly as influential as many of his other contributions.

Ready to Think Deeply?

Learn what it means to think like a philosopher with the MasterClass Annual Membership. Dr. Cornel West, one of the world’s most provocative intellects, will guide you through fundamental questions about what it means to be human and how to best love your community.