Normative Economics in Comparison to Positive Economics

Written by MasterClass

Last updated: Oct 5, 2022 • 4 min read

Normative economists believe economics should be more than a social science. Instead of describing the economy as it is, they suggest people instead decide on the ethical desirability of specific economic outcomes and then tailor their policies around these goals. In many cases, the broader goal of normative economics is to maximize social well-being.

Learn From the Best

What Is Normative Economics?

Normative economics is, in essence, an economic theory of justice. Rather than taking a detached, mathematical approach to analyzing the political economy, normative economists believe they have a duty to espouse a specific ethical point of view in their analysis. By doing so, they hope to influence policymakers to implement specific laws, incentives, and regulations to bring about what they see as the most desirable economic situation for a given society.

In contrast to normative economists, positive economists believe ethics have no place in either macroeconomic or microeconomic research. Instead, they insist the economist’s job is merely to assess data and allow policymakers to do with it what they will, rather than inject their own moral viewpoints into any given decision or scenario.

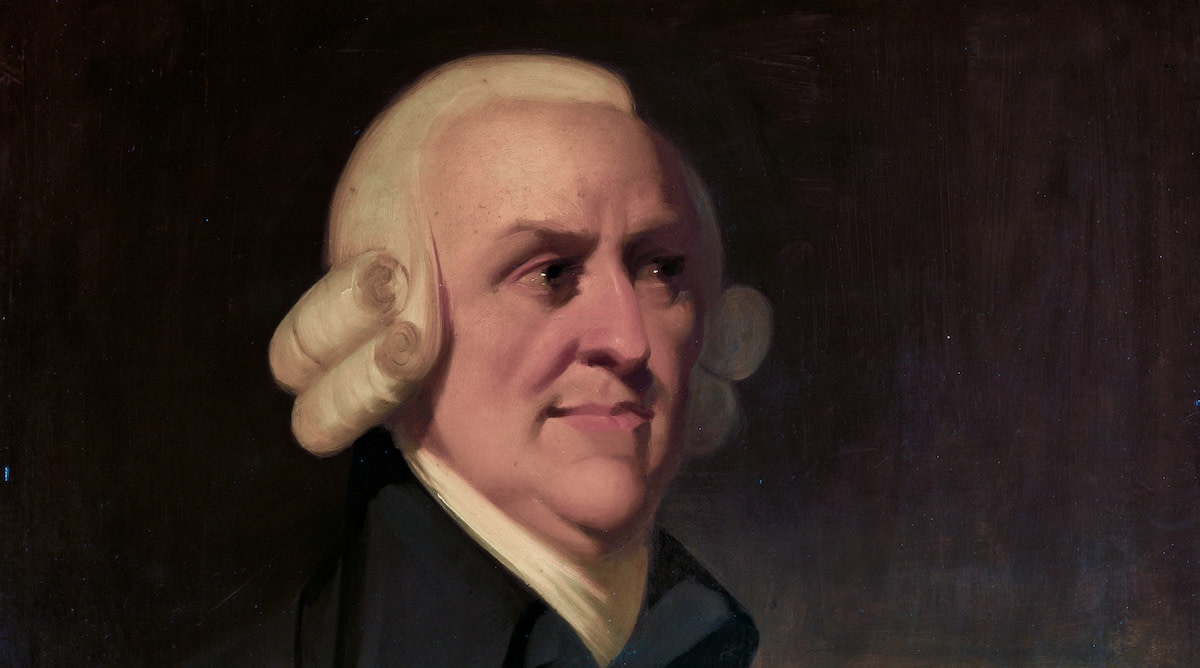

Who Created Normative Economics?

The eighteenth-century economist Adam Smith deserves attribution for spearheading this branch of economics. While his book The Wealth of Nations takes a more positive (or descriptive) approach to the economy, his prior work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, took a more prescriptive and normative stance on economic and ethical issues.

In the early twentieth century, normative economics split off into various subsidiary fields like welfare economics and social choice theory. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies, as well as President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society initiatives, depended in part on normative economic theorems about the common good, such as the Pareto principle.

Normative economists like Amartya Sen have expanded on these ideas in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. By contrast, prominent economic figures like Milton Friedman advocated for leaving ethical norms and moral philosophy out of the discipline as a whole. Positive economists like this tend to want their field to stay largely data-centric and impersonal.

Normative Economics vs. Positive Economics: 3 Areas of Difference

Normative economists take a much different approach to their field than their positive economist counterparts. Here is how the two schools of thought approach economic issues:

- 1. Ethics-driven vs. data-driven: Normative economists believe ethics should drive economic analysis, whereas positive economists place a larger emphasis on simply assessing aggregate data. While both types of economists have a vested interest in conveying their viewpoints as self-evident and objective, rather than ideologically driven, normative economists are more open about their potential biases.

- 2. “Ought” vs. “is”: A normative economic statement is more likely to include words like “ought” or “should,” while positive statements rely more heavily on words like “is” and “are.” This is because normative economists view injecting value judgments and moral axioms into their research as their duty, whereas positive economists think of this practice as anathema to what they perceive as hard and fast economic science.

- 3. Prescriptive vs. descriptive: The core methodology of analysis is different for normative and positive economists. The former group believes economic policy should align with prior ethical decision-making, but the latter group thinks the purpose of economics is to describe data rather than prescribe outcomes. In other words, a normative economist would likely provide an opinion about the ethical ramifications of any cost-benefit analysis, but a positive economist would not.

Examples of Normative Economics

A normative economic approach remains common in many areas of interest to the broader political economy. Consider these key examples:

- Capitalism and socialism: Capitalists and socialists both talk about their preferred economic systems as if they are inevitable outgrowths of reality itself. In actuality, both offer normative prescriptions about the allocation of wealth and the relationship between labor and capital. Entire societies build their economies out of these baseline prescriptions.

- Carbon emissions policies: Many normative economists see the current situation with climate change as an unsustainable state of affairs. As such, they insist on cap-and-trade policies, carbon taxes, environmental regulations, and so on as both economically advisable and ethically necessary. In contrast, positive economists would aim to project the effects these policies would likely have on the economy without taking an explicit moral stance on them.

- Forms of taxation: Different normative economists will have different beliefs about taxation as a matter of public policy. Some might insist it’s essential to tax the rich and redistribute their wealth to the poor, while others could proclaim the only ethical way forward is a flat tax for people of every economic bracket. Both economic models rely on beliefs in their respective moral prescriptions.

- Public vs. private health care: Some people believe the government has a duty to make universal health care an economic policy, whereas others think it’s essential to keep it in the realm of private expenditure. Normative economists will argue their case on either side via both ethical entreaties and economic data.

- Welfare spending: Social welfare economics is often a subject of political contention. Certain normative economists believe people should receive welfare free of stipulations beyond need, whereas others might say any welfare program must come with incentives for people to reenter the workforce (or even penalties if they do not).

Learn More

Get the MasterClass Annual Membership for exclusive access to video lessons taught by the world’s best, including Paul Krugman, Doris Kearns Goodwin, Ron Finley, Jane Goodall, and more.