Learn About Documentary Filmmaking: How to Research a Documentary Film With Tips and Advice From Ken Burns

Written by MasterClass

Last updated: Sep 24, 2021 • 5 min read

Documentary filmmaking requires research to provide the context, footage and other visuals, narration, and interviews that will appear in the film. There are several types of research that documentary filmmakers might undertake, including archival research, academic research, and in-person interviews.

Learn From the Best

What Is Documentary Filmmaking?

Documentary filmmaking is a non-fiction style of filmmaking that seeks to document some aspect of reality. This can be done for education, preservation, and entertainment purposes.

Documentary filmmakers often choose subject matter they are passionate about, and a great documentary can be about any non-fiction, real-world subject. Indeed, sometimes the truth is stranger than fiction—and often more interesting. Many filmmakers are realizing this, choosing to delve into nonfiction narratives and bringing them to both the big and small screen. In fact, we are in the midst of a renaissance in documentary storytelling that has been going strong for more than three decades.

What Is the Difference Between a Documentary Film and a Feature Film?

There are a number of key differences between these two different types of film.

- Feature films deal with fiction and fictionalized events. The main purpose of a feature film is to entertain.

- Documentaries deal exclusively with facts and real-life events. The main purpose of a documentary is to inform and educate.

- Despite their differences, both feature films and documentaries use cinematography and follow a script.

Why Is Research Important In Documentary Filmmaking?

Good documentary filmmaking requires research, in fact by definition the documentary filmmaking process requires research into the subject it seeks to document.

- Whatever the subject of your documentary—from skateboarding to the Korean War or tofu—it will always require research. In order to document actual events, histories, people, and cultures, you must find the documents, people, and objects that will tell your story.

- Research is necessary for the raw visual materials that will ultimately become the documentary as well as provide you, the filmmaker, the context necessary to understand, interpret, and share the subject of your film.

- Research is also important to organize and plan out your documentary. It will also bride your documentary’s storyline, which at some point will be organized and illustrated on a storyboard using your research. From there, you will need to research your shot list.

How to Research a Documentary Film Step 1: Pick the Type and Length of Your Film

Before you undertake research for your documentary, you must first decide what documentary type you are making. For example, your documentary can be historical, or it can be biographical.

Next, you must decide on the length of your documentary.

- A short documentary is generally defined as having a running time of 40 minutes or less. This is often a wise choice for those embarking on their first documentary film projects.

- A feature-length documentary is generally defined as having a running time of over 40 minutes. This is better suited for seasoned filmmakers.

How to Research a Documentary Film Step 2: Conduct Archival Research

Now that you know the type of documentary you want to make, the subject, and the length, you are ready to fully undertake research.

This often begins with archival research. Archives have a diverse range of different research materials, including:

- Still photos, footage, newspapers, and online articles

- Paintings, etchings, sketches

- Letters, journals, and diaries

- Governmental documents

Once you have obtained relevant and interesting archival materials, investigate for deeper sources. For example: with a newsreel, you should seek out the raw footage and b-roll from which that reel was edited to uncover material that was unused at the time but is nonetheless potentially useful to you.

How to Research a Documentary Film Step 3: Identify Your On-Camera Subjects

Following your archival research, you now know roughly what kind of interview subjects you will need. Identifying the documentary’s interview subjects or talking heads is a crucial step. These individuals will be interviewed on camera during your film.

There are two types of on-camera subjects:

- Academic experts who will provide the viewer with insight into the events, an expert opinion that will inform the audience’s understanding of the events. These sources are generally easily convinced to participate because they are eager to share their expertise. Doing secondary research at an academic library will tell you who the authorities in the time period are, and these people are all possible sources for your film.

- Primary source witnesses to the historical events described. If the documentary is a time from which there are currently no survivors, this is obviously not an option. In these cases, primary, contemporary sources like observer accounts, diaries, letters, and journals (all products of archival research) become all the more important.

Ken Burns’s Tips For Researching For a Documentary Film

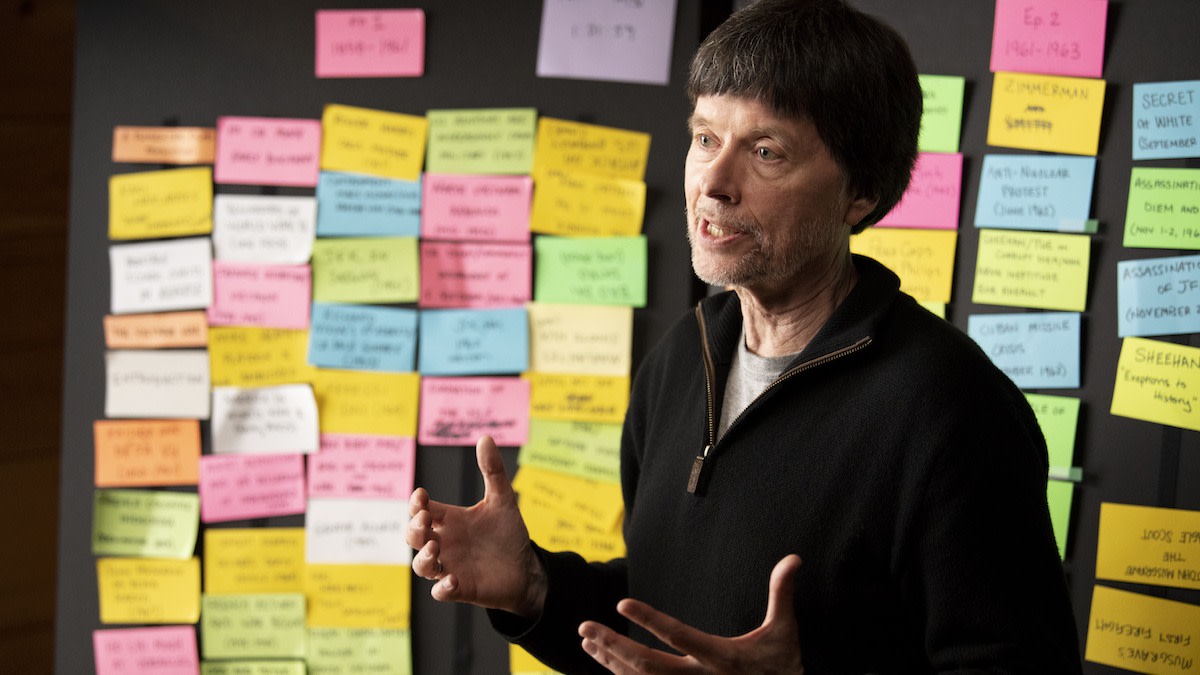

When award-winning documentarian Ken Burns talks about documentary filmmaking, people listen—from Hollywood all the way to Sundance.

Burns’s documentaries cover United States history—from New York during Prohibition to California during the Depression—and have a distinct point of view. Often, this point of view favors the social history of everyday people living through some of the most significant events in America’s history.

Burns is the first to point out that his impressive resume, however, is only possible with diligent, extensive, and adaptable research. And this begins with archival research.

Refer back to this tip list next time you’re starting to delve into your own archival research.

- When it comes to archival research, Burns advises that more is more. Think of archival research as making maple syrup—you need 40 gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup.

- You should collect much more than you think you need—at least 40 times the material you ultimately plan to use in your film. Gather at your fingertips all available variations in order to explore every artistic and dramatic possibility. Only with a 40 or 50 to one ratio will you be able to distill the essence of your story.

- Search for archival material in places you wouldn’t initially think to look. Ask about collections that no one else asks about.

- Remember, you are a detective, so follow every lead as far as it will go. Don’t limit yourself to easy-to-access material about well-known historical figures. Dig for evidence of what life was like for ordinary people as well.

- Persistence is crucial to gathering so much material. Burns is especially tenacious when approaching individuals who are reluctant to share personal artifacts. He relates one example where he spent six months wooing an individual to share material for his Jazz series until finally the person was convinced.

- Because it often takes a long time to find the perfect artifact, never limit yourself to one discrete research stage. Keep investigating sources throughout your process, even during post-production and film editing, finishing, and even early showings at film festivals. You never know when you might strike storytelling gold, something that is worth opening your film back up to include.

Whether you’re a budding documentarian or have dreams of changing the world, navigating the world of documentary filmmaking requires plenty of practice and a healthy dose of patience. No one knows this better than legendary documentarian Ken Burns, whose 2017 film, The Vietnam War, paints an intimate and revealing portrait of history. In Ken Burns’s MasterClass on documentary filmmaking, the Academy Award nominee provides valuable insight into his methodology and talent for distilling vast research and complex truths into compelling narratives.

Want to become a better documentary filmmaker? The MasterClass Annual Membership provides exclusive video lessons from master documentarians including Ken Burns and Werner Herzog.