Ken Burns Shares 7 Tips for Structuring a Documentary

Written by MasterClass

Last updated: Jun 7, 2021 • 6 min read

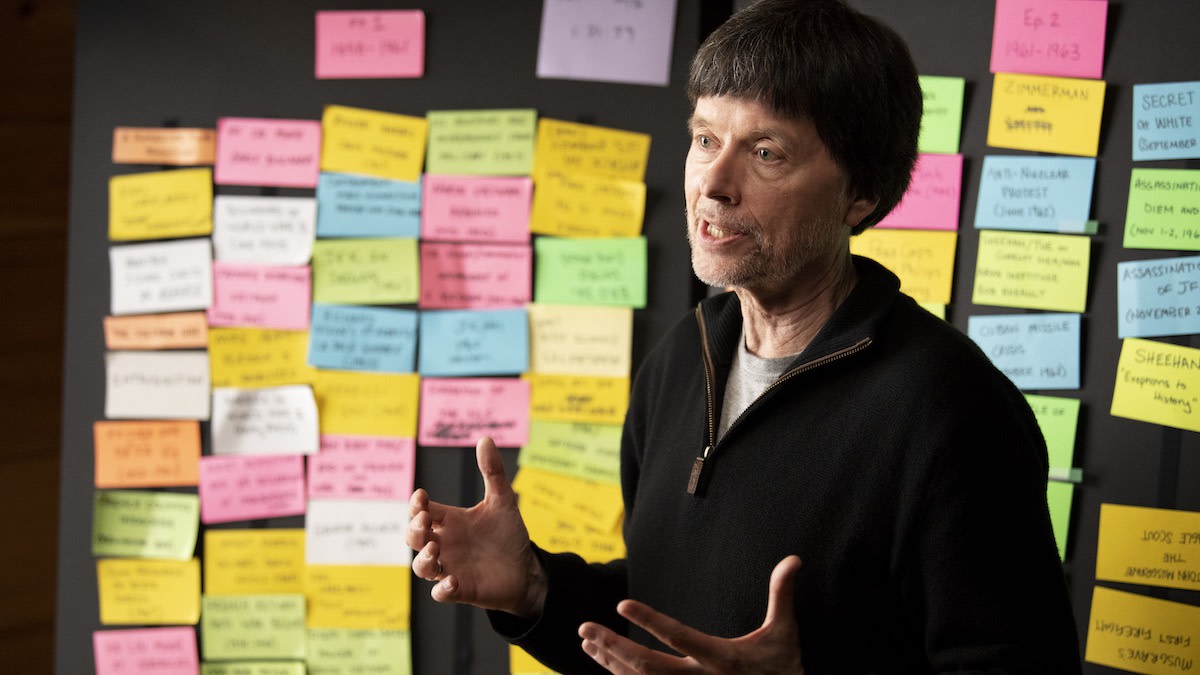

World-class documentarian Ken Burns knows how to utilize narrative structure to draw in audiences. Burns offers tips on crafting an engaging documentary structure.

Learn From the Best

Documentary filmmaking can help us learn where the truth lies in past or current events. Documentarians create non-fiction films that present a real-life truth in cinematic form, using various techniques and compelling story structure to draw audiences in and make them care about the subject matter on camera. When creating your documentary feature or short film, the type of storyline you’re trying to emphasize can affect the story you want to tell.

A Brief Introduction to Ken Burns

Ken Burns has been making documentary films for more than 40 years. Ken’s films have been honored with dozens of major awards, including 15 Emmy Awards, two Grammy Awards, and two Oscar nominations. In September of 2008, at the News & Documentary Emmy Awards, Ken was honored by the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences with a Lifetime Achievement Award. Since making his first documentary, the Academy Award-nominated Brooklyn Bridge in 1981, Ken has gone on to direct and produce some of the most acclaimed historical feature documentaries ever made, including The Statue of Liberty (1985), Huey Long (1985), The Civil War (1990), Baseball (1994), Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery (1997), Jazz (2001), The War (2007), The Dust Bowl (2012), Jackie Robinson (2016), and Country Music (2019). His latest documentary for PBS, The Gene: An Intimate History, was released in April 2020.

Ken Burns Details How to Hook Your Audience Immediately

Ken Burns’s 7 Tips for Structuring a Documentary

The best way to keep someone in place watching a film is an authentic engagement with the narrative arc. Documentary filmmakers need to be able to tell an engaging story, and engaging storytelling is all about conflict. It's about not knowing how something's going to turn out. You keep reading or watching because it may not turn out the way you know it did. Check out world-class documentarian Ken Burns’s tips on crafting a narrative structure:

- 1. Embrace the laws of storytelling. Whether you’re making a documentary or writing a feature film, every filmmaker is under the power of the laws of storytelling. The best documentary scripts have a beginning, the middle, and end, main characters, antagonist, protagonist, character development, climax, dénouement—all of these things work on us. Documentary storytelling also follows these laws. Instead of the documentary necessarily being didactic and educational and politically advocating, it can also tell a story using the same expositional tools as a feature film. Then you've got the possibility of moving people at that same level, and you have the added advantage of it being true.

- 2. Keep rearranging structure until it works. Everything is itself an arc. Within a sentence that you write, there's an arc to the sentence. Within a paragraph or a comment by someone, there's an arc. A scene has its own arc. A collection of scenes within an episode have their arc. When you're trying to do a documentary about true subjects, whether it's history or not, you're always in a battle between the obvious demands of story and the fact that human life often defies that. What you're trying to do is constantly refine the arcs that exist. It may be as precise as changing a word in a sentence. At any moment, you have to be free to give up something or to think of a new relationship. To rewrite a whole thing, which you’ll do often. To change. To take out the talking head that's seemingly the key to it, put in somebody new, or make a first-person voice a bigger part of that role and move that voice. You want to keep the scaffolding and false workaround of that construction project up long enough that you're very sure that the building is gorgeous and will stand by itself.

- 3. Hook your audience immediately. The beginnings become the most artful, the most challenging, the most critical moments of the film. It's the first note. How do you strike that strong note that invites your viewer into what you're going to do? In every film, you must look for a way to allow an audience space to leave the world that they are in. Filmmakers need to ask themselves, "How do I transit you from your incredibly busy and compelling life, and bring you to this moment?” You can't force people into it by exaggerated drama. The first shots and the first scenes are the establishments of a covenant between you and your audience. You’re asking for the extraordinary gift of the audience’s attention, and then rewarding that attention for the next two hours or the next 18 hours.

- 4. Introduce large stories through small details. For example, in Ken’s The Civil War (1990), he shares the story of Wilmer McLean: “By the summer of 1861, Wilmer McLean had had enough. The First Battle of Bull Run, or Manassas, as the Confederates called it, had raged across the aging Virginian's farmland, a Union shell exploding in the summer kitchen. Now, McLean moved far south and west of Richmond, out of harm’s way, he prayed, to a dusty little crossroads called Appomattox Courthouse. It was there, three and a half years later, that Lee surrendered to Grant, and Wilmer McLean could rightfully say, "The war began in my front yard and ended in my front parlor." This memory was something of an ending footnote, but Ken chose to put it at the very beginning. You cannot discount how important the subtlest and most ordinary quotidian of events will be in the larger scheme of things.

- 5. Use chronology as a compass. According to Ken, the central important part of narrative is chronology. As Shelby Foote once told Ken, "God is the greatest dramatist." Things naturally happen in chronological order. That doesn’t mean you can’t do a flashback. Sometimes, you have to initiate a hugely effective flashback—and sometimes it doesn’t work. Sometimes, you have to move it to the introduction. That’s always the possibility, where you return to straight chronology. Our storyboards remind us that we really can't move anything, because we're trying to keep it in chronology.

- 6. Boil the pot. There’s no fundamental law of the climax. You know that something happens. However, it’s not always the big crashing event that we think of when we talk about climaxes. Sometimes, it's a subtler sort of thing. Sometimes, it's very obvious and dramatic. At some point, the episode becomes like a pot boiling. Then, when it boils, you've got a release, and it comes in so many different fashions. It doesn't mean you can't articulate it or talk about it, but somehow there has to be a kind of breathing in and out that you do that becomes more intuitive.

- 7. Send them home safe. Nothing is redeeming about the loss of three million people in the Vietnam War, Ken says. The artist takes you deep into this hell, and it's the obligation of the artist to lead you out, Ken explains. There doesn’t need to be closure, but perhaps a little bit of peace. So you permit a dismount. With the Vietnam War (2017), Ken wanted to remind the audience that throughout this horror story, there were moments of love, sacrifice, courage, and generosity—and that in the end, the finest of all those things, love and reconciliation, can take place.

Want to Learn More About Film?

Become a better filmmaker with the MasterClass Annual Membership. Gain access to exclusive video lessons taught by film masters, including Ken Burns, Spike Lee, David Lynch, Shonda Rhimes, Jodie Foster, Martin Scorsese, and more.