Emancipation Proclamation: History, Evolution, and Impact

Written by MasterClass

Last updated: Sep 13, 2022 • 3 min read

The Emancipation Proclamation is a foundational document in the history of abolition in the United States. However, its immediate effects were not as straightforward as simply ending slavery.

Learn From the Best

What Is the Emancipation Proclamation?

The Emancipation Proclamation—issued by President Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War on September 22, 1862, to take effect on January 1, 1863—nominally freed enslaved people in Confederate states actively involved in the rebellion against the Union. The Proclamation also allowed Black men to serve as soldiers in the Union Army and Navy for the first time.

While it would have a monumental impact on American history, the Proclamation was more of a symbolic document than a legal one. The Confederacy had no incentive to heed an edict authored by their primary enemy in the Civil War, especially when they were so geographically and philosophically distant from the North.

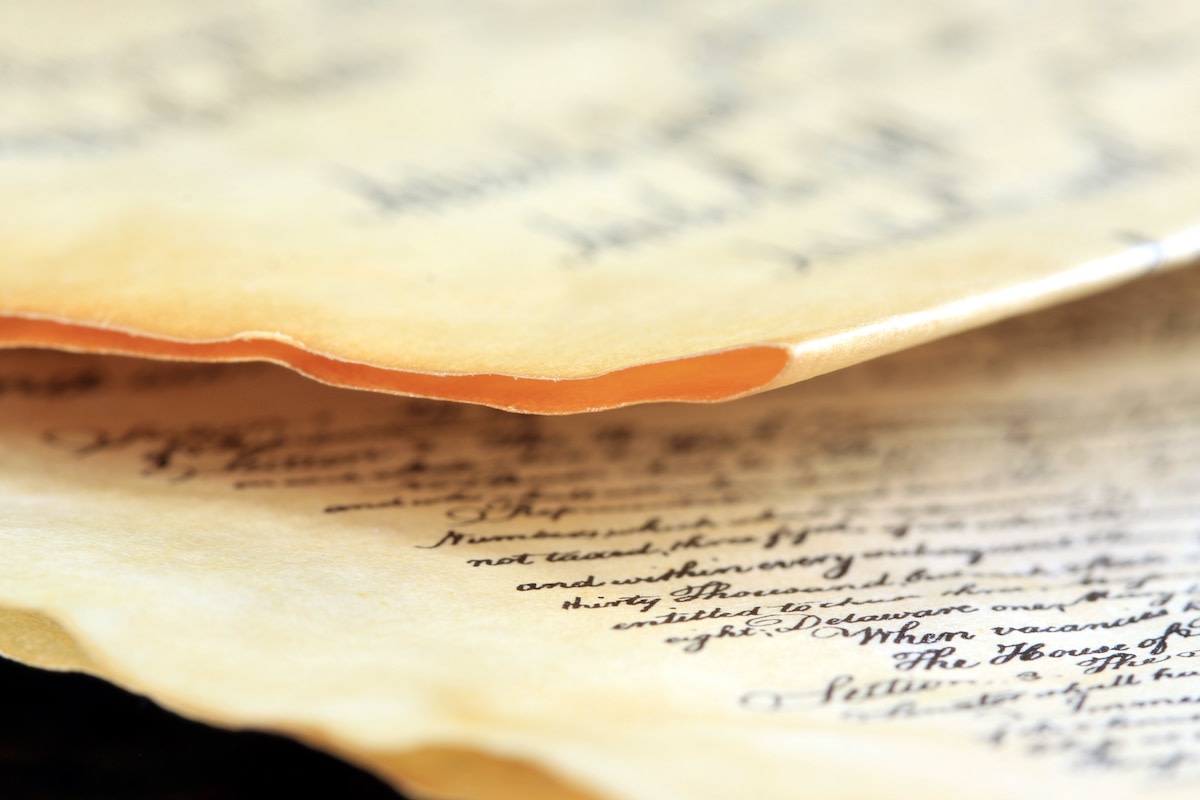

The final Emancipation Proclamation is currently part of the National Archives, while the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation resides in the New York State Library. The Library of Congress hosts an online reproduction of the final document on their official website.

Did the Emancipation Proclamation Free All Enslaved Peoples?

The Proclamation did not free all enslaved peoples in the Southern or Northern states. Instead, the Proclamation specifically exempted the border slave states of Maryland, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri and Confederate territory, which federal troops controlled (for example, certain parts of Louisiana.) Slavery did not fully end in the new state of West Virginia until 1865.

The Leadup to the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

President Abraham Lincoln made it clear in statements before and after secession that the federal government’s primary goal in the war effort would be to preserve the Union rather than free enslaved peoples in the South. He didn’t even believe the Constitution granted him the authority to do so, either as president or commander-in-chief.

Instead, he focused his efforts on ensuring that newly added states would be free states—a set of priorities central to the establishment of the Republican Party several years before. Nevertheless, Lincoln did make some movement toward emancipation as the war pushed on, primarily due to abolitionists who lobbied fiercely to make it a central tenet of the Union’s drive south.

In July 1862, Lincoln signed the Militia Act and the Confiscation Act, a pair of laws that allowed Black labor in the armed forces and immediately freed any enslaved people seized from members of the Confederacy.

How Did the Emancipation Proclamation Evolve?

Lincoln’s views on the best way to deal with slavery changed significantly during his lifetime. By the time he began drafting the Proclamation, he had already tried and failed to convince the border states on a plan for gradual emancipation through “emigration and colonization.”

Lincoln wrote the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in July 1862. Still, members of his cabinet (most notably Secretary of State William H. Seward) pressured him to hold off on issuing it until after a significant Union victory. The Battle of Antietam provided the opportunity. When no Southern states took him up on the offer to rejoin the Union detailed in his preliminary Proclamation, he signed the final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1 of the following year in Washington, DC.

Impact of the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, while legally toothless at the time, proved to be a shrewd war measure as well as a guiding force after the end of the war:

- Black participation in the Civil War: The lifting of the ban on Black men in the military led to almost 200,000 Black soldiers joining the Union forces as liberators—a significant boon to the war effort.

- A major shift in the focus of the Civil War: The Emancipation Proclamation made the Civil War explicitly about freeing enslaved people, turning the Union drive into an act of justice. In addition to the boost of morale at home, from a political standpoint, this provided the persuasive power Lincoln needed to keep England and France from supporting the Confederacy.

- The beginning of abolition: While the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t immediately end slavery (word of emancipation wasn’t spread through Texas, for example, until 1865), it did get the ball rolling. Soon after the issuance of the Proclamation, opponents of slavery in Congress used the momentum to start work on the 13th Amendment, which would mark the end of slavery after its ratification in 1865.

Learn More About Black History

There’s a lot of information that history textbooks don’t cover, including the ways in which systems of inequality continue to impact everyday life. With the MasterClass Annual Membership, get access to exclusive lessons from Angela Davis, Dr. Cornel West, Jelani Cobb, John McWhorter, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Nikole Hannah-Jones, and Sherrilyn Ifill to learn about the forces that have influenced race in the United States.